Not Your Mokopuna, Erica: White Spaces Rebranded. The New Face of the Same Old Racism

This is a slightly amended version of my presentation to the UpliftED Conference hosted by the Aotearoa Educators’ Collective (AEC) in Wellington on 31 October 2025.

Picture this…

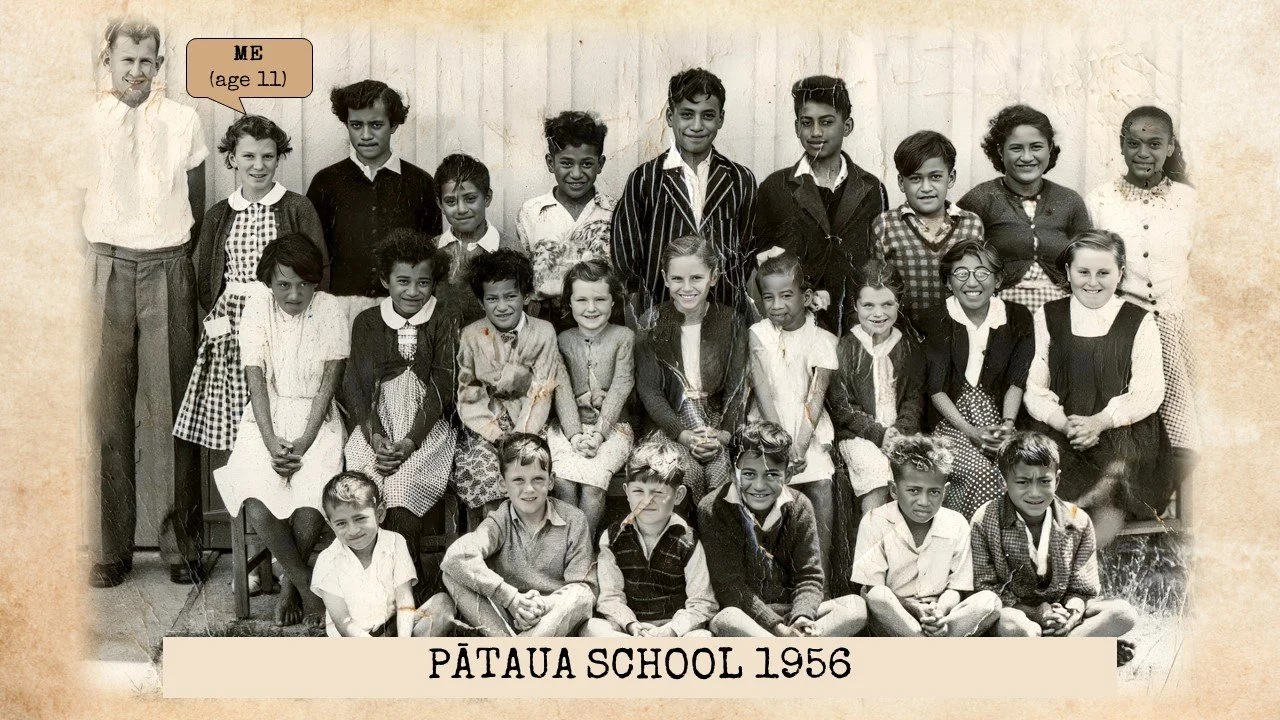

It’s the 7th of February 1952. Very inconveniently, my six-year-old self thought, King George the 6th, disrupted my eagerly anticipated first day at Pātaua School by dying in the early hours of the morning – and schools across the country closed in respect.

Now, I’ve been scoping the room over the last two days, and I doubt too many of us are in the position to remember education that far back – or to have been actively engaged in it for as long —so I’m taking advantage of my geriatric status and my long memory, to remind us, and particularly our Minister of Education, just how many times we’ve been here before.

Back at Pātaua School, in the one-room building, there were never more than 25 of us, from what we called Primer One to Standard 6, and most of the students were Māori.

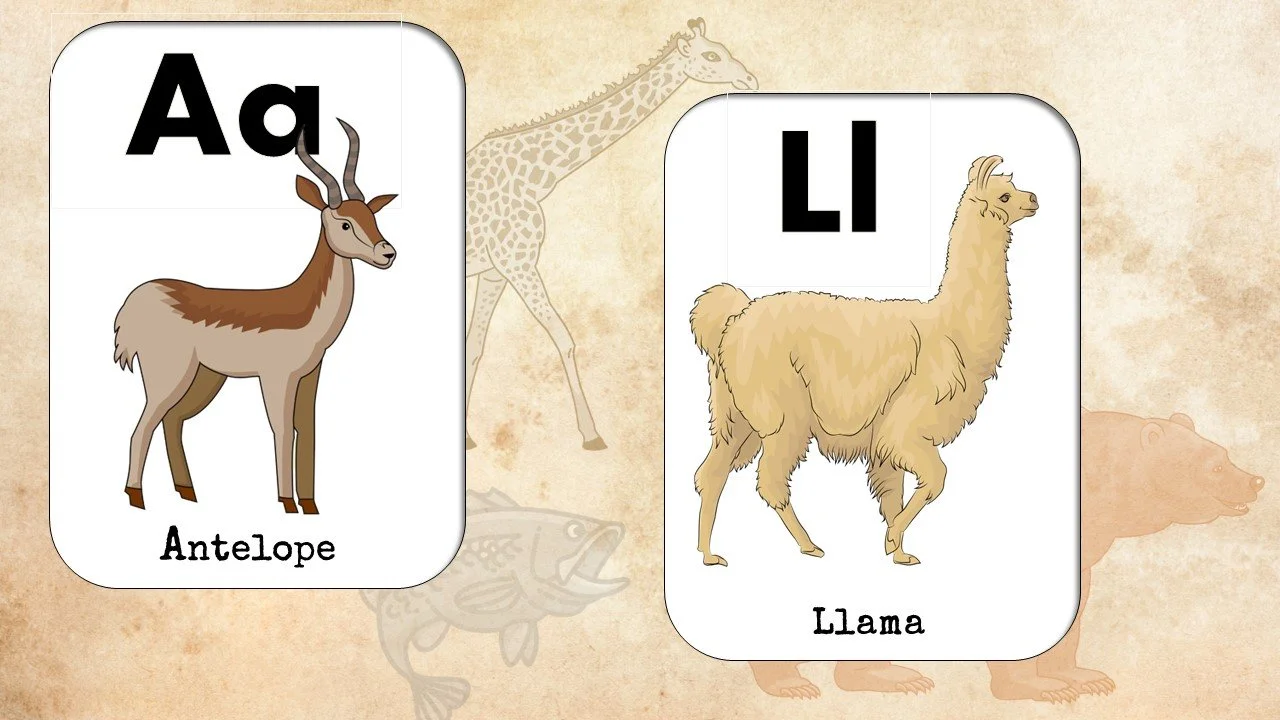

Every morning, without fail, we recited our times tables and our animal-themed phonics chart. I can still see the pictures on that chart as we droned “A is for Antelope. L is for Llama.”

Antelopes and Llamas

It took me many years to recognise the vast white spaces in my education.

Antelopes and llamas. We’d never seen either of them, possibly never would, but we could chant them perfectly. That was education. That was literacy for children of Ngati Korora and Te Waiariki, who had grown up on their own whenua and who knew who they were, before their schooling experience intentionally changed that.

It took me many years to recognise the vast white spaces in my education—at Pātaua School for six years, later at Whangārei Girls’ High School, in my teacher training at Ardmore Teachers’ College, and in my own early years of teaching.

That lesson didn’t hit home until my own children, who identify strongly as Māori through their father’s whakapapa, entered secondary school, but that one room at Pātaua, filled with brown kids, was my first glaringly white space — a space where Whiteness was the air we breathed but never named. where Māori children learned that the world that mattered was somewhere else, and someone else’s.

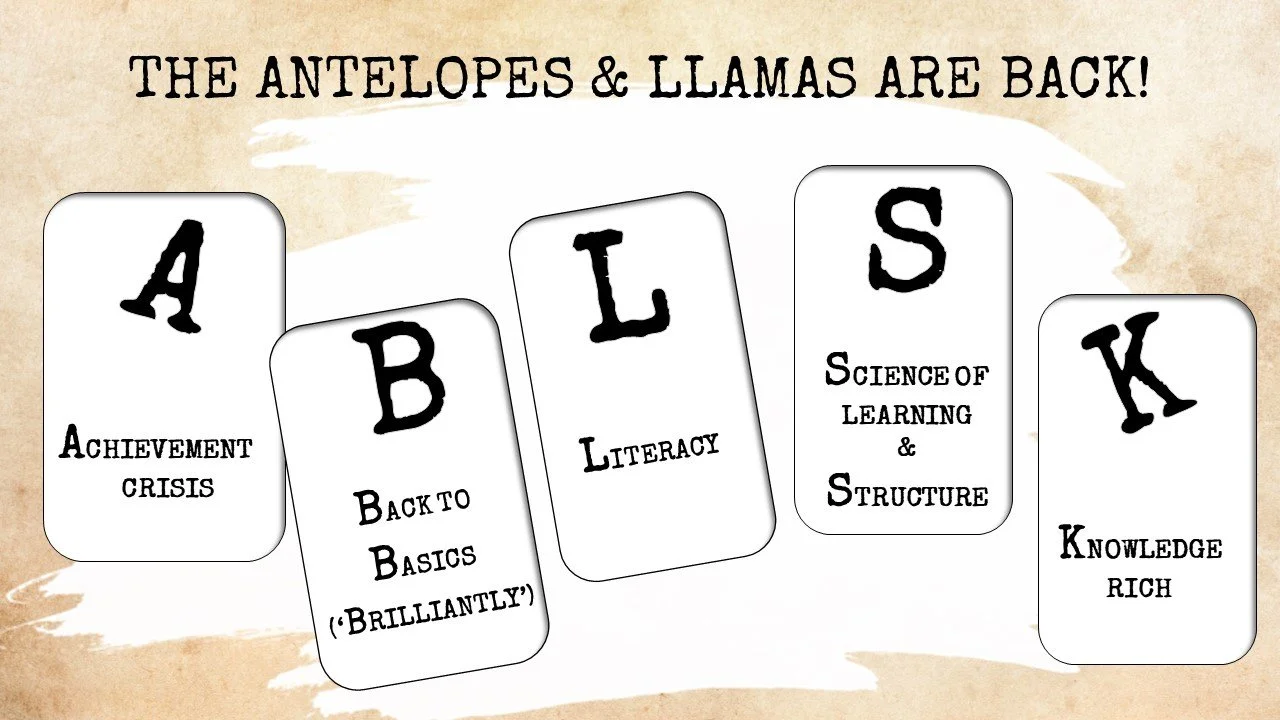

Seventy-three years later, the antelopes and llamas are back. They’ve changed their names — “structured literacy and maths,” “the science of learning,” “a knowledge-rich curriculum,” “back to basics, an achievement crisis.” But make no mistake, they are still antelopes and llamas and it’s the same white space, just with a new layer of white paint.

Let’s look at some of those changes:

the throwing out of NCEA,

the negating of years of promising curriculum development culminating in Te Mātaiaho

the blatant violation of public service guidelines to favour an elite few,

the supremacy, the privilege, and the racism in the erasure of Māori words from early readers,

the erasure of Māori and Pasifika authors in favour of Shakespeare,

In fact, the erasure of Māori, full-stop – Te Tiriti from the Education and Training Act, removing the requirement for school Boards to give effect to it, and the removal of references to Te Tiriti in all policy. That’s the short list!

I was there!

And the point is - we’ve been there and done that before, and I was there!

In my own secondary schooling at Whangārei Girls’ High School at the age of 12, I sat entrance tests that funnelled me into the ‘professional’ stream, completely reversing my experience from Pātaua, because all the Māori girls ended up in what was called the ‘Commercial’ classes. Nothing to do with economics or business, just learning how to type, take shorthand, and be of service. Those labels and those expectations followed us throughout our secondary schooling and into our working lives.

Do you think that throwing out of NCEA, Erica, because you don’t understand it as a parent (in the secondary school I led – all parents understood it perfectly, by the way) and replacing it with a process where students have to pass four out of five subjects—where their results are graded out of 100—is a new idea?

Nope! In 1960, I passed School Certificate in five subjects, scraping through with just 53% in Maths, and I watched many of my friends locked into having to repeat the fifth form until they passed. It was demoralising then, and it will be again, as young people fail their Foundational Skills literacy and numeracy assessment in Year 11 and get syphoned off at 15 or 16 years of age into vocational courses just like the 1960s.

And which young people will still be the most affected – that’s right, Erica, not your mokopuna!

In 1961, I had my University Entrance qualification accredited, awarded based on my performance throughout my final year of secondary school. No exams, Erica! It might have worked for me, but it was still a white space where this Pākehā girl from Pātaua learned Latin, French, and German, and went off to Teachers’ College, and most of the Māori students I grew up with just left school and went home.

That was exactly the reason for introducing NCEA. School Certificate was an exam-based one-size-fits-all approach, and University Entrance exams created a bottleneck that many students, particularly Māori and those marginalised and minoritised by our system, couldn’t get through. Young people were leaving school early, unable to find jobs, ill-equipped for the transferable skills required in a technological world.

Of course, it has flaws, but NCEA has enabled my fluent Māori-speaking mokopuna to achieve degrees in teaching and performing arts, to run successful businesses in media production, to lead organisations, to travel all over the world, become content creators, producers, directors, and consultants, artists, tattooists, mau rākau exponents, and athletes. In all of these roles, their bilingual skills in Māori and English are their greatest strength, unlike the languages I learned and have never used. That creative depth and breadth will never be delivered by a narrowed return to the 1960s.

Integration = Erasure

Let’s take a closer look at the current intentional erasing of anything Māori from our education landscape. That, too, is nothing new!

The deliberate removal of Māori from education policy and thinking was implemented following the Hunn Report in 1961, two years before I started my teaching career at Hikurangi Primary School, still oblivious to the white space I entered and became complicit in replicating. The Hunn Report was the first official document to make explicit the disparities between Māori and Pākehā—so no, Erica, this isn’t something you newly uncovered in 2024 and decided to call a crisis! And guess what? The government’s response then was just like yours now.

Hunn failed to question the moral legitimacy of an education system that steered Māori away from professional careers and into manual labour, nor did he acknowledge that structural inequality and unequal power relations lay at the root of the issue. Instead, he simply recommended replacing the policy of assimilation with one of integration.

Never mind what Dr Ranginui Walker called “the whakapapa of the gaps,” the relationship between power and knowledge, and the role of the state in generating what counts as knowledge. Under the policy of integration, Hunn proposed that something he called ‘evolution’ would integrate Māori and Pākehā so rapidly that “in two generations the process would be nigh-on complete. There would be some preservation of Māori culture, but most of it, he decided, “had already departed, and only the fittest elements would survive.” Let’s make NO mistake – integration meant erasure!

In the year I left teachers’ college, along came the Currie Report – the Report of the Commission on Education in New Zealand that FOR THE FIRST TIME, officially rejected the idea that there was a difference in intellectual potential between Māori and Pākehā—but doubled-down on deficit-thinking nonetheless with its conclusion that:

Too many [Māori children] live in large families in inadequately sized and even primitive houses, lacking privacy, quiet, and even light for study; too often there is a dearth of books, pictures, educative material generally, to stimulate the growing child.

Policy Driven by Deficit Thinking

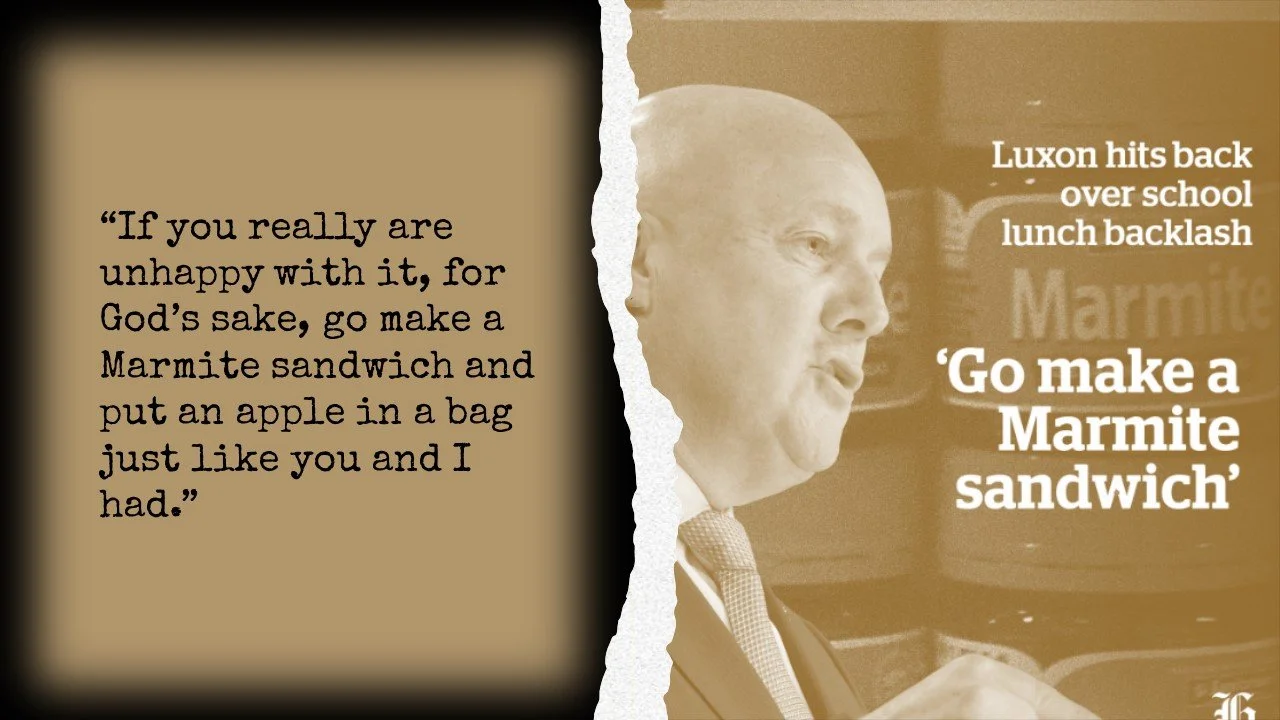

But are we really done with deficit thinking 63 years after Currie? Luxon’s condescending advice over the school lunch fiasco to “Go make a Marmite sandwich,” and his recent “get off the couch, stop playing PlayStation, and go find a job” comments, would say we are not!

The talk from this government of “raising Māori achievement” is code for fixing Māori learners, not fixing the system. It echoes the thinking of American academic E. D. Hirsch, whose 1996 book The Schools We Need and Why We Don’t Have Them argues that, to help children from “underprivileged homes,” schools must directly teach them the “knowledge which the children of privilege gain indirectly at home.”

In other words, working-class and Māori children are seen as blank slates, waiting for schools to fill their supposed cultural void. This is deficit thinking disguised as educational science — the very theory, Erica, that you proudly called “the complete foundation” for your curriculum reforms. On stage at the No Boundaries, Just Possibilities Conference, you embarrassingly fan-girled E.D. Hirsch and brandished his book — the one you’ve said you read “on holiday at the beach” — as your inspiration. That same book positions Māori and working-class knowledge as something to be replaced rather than respected.

Back in the 60s, the fear of a Pākehā backlash to two outcomes of the Hunn Report—the establishment of the Māori Education Foundation and the National Advisory Committee on Māori Education—was real. Sound familiar? It should. Today, we see the same backlash dressed in modern neoliberal language: Hobson’s Pledge, the New Zealand Initiative, Rata, Seymour, and Luxon — all desperate to reassure their privileged, right-wing, libertarian voting base that Māori success must be managed within their white comfort zones.

What is the Question?

Ranginui Walker writes that “in the 1970s, to circumvent opposition to the insertion of Māori language and culture into the school curriculum, Māori intellectuals redefined assimilation and integration as taha Māori.” Dr Wally Penetito asked, “If taha Māori is the answer, what is the question?”

And there I was, in the 1980s, at Clover Park Intermediate in Otara in South Auckland, leading the development of the first ‘taha Māori’ unit at an intermediate school anywhere in the country—and thinking I was doing a great thing—with no idea that there should be a question—complicit in, and blind to, my own white spaces!

I was perfectly capable of reciting my Pātaua School phonics chart and my times tables by rote. Yet, in spite of the fact that I was a minority at Pātaua, nothing in that education opened my eyes or my mind to racism, integration, assimilation, multiculturalism, taha Māori, and the tools of colonisation. It was all antelopes and llamas—and no different from the situation we have right now!

Meanwhile, Māori parents who have never stopped protesting were building Kōhanga Reo on marae floors and demanding Kura Kaupapa Māori without government support because the state had refused to listen. They weren’t asking to be included in white spaces; they were creating their own.

Very involved in that movement was none other than Elizabeth Rata, a Pākehā academic, who was once part of the original Kura Kaupapa Māori Working Party and secretary to the kōhanga reo whānau group developing Māori-medium education. However, as Dr Leonie Pihama points out, Rata’s later attacks on Māori educational movements stem from a “politics of resentment.” Rata now promotes her own “knowledge-rich” professional-development programmes, opposes the indigenisation of universities, and was among the seven White academics who signed the infamous Auckland University letter rejecting parity between mātauranga Māori and Western science in the school curriculum

So, I have to say, Erica —seriously —if Rata is your answer, it’s terrifying to think what your question is! But, I have one!

Can you please explain how this sort of racist, outdated influence, that is not only advising education policy, but actually writing curriculum, can possibly benefit my mokopuna Māori?

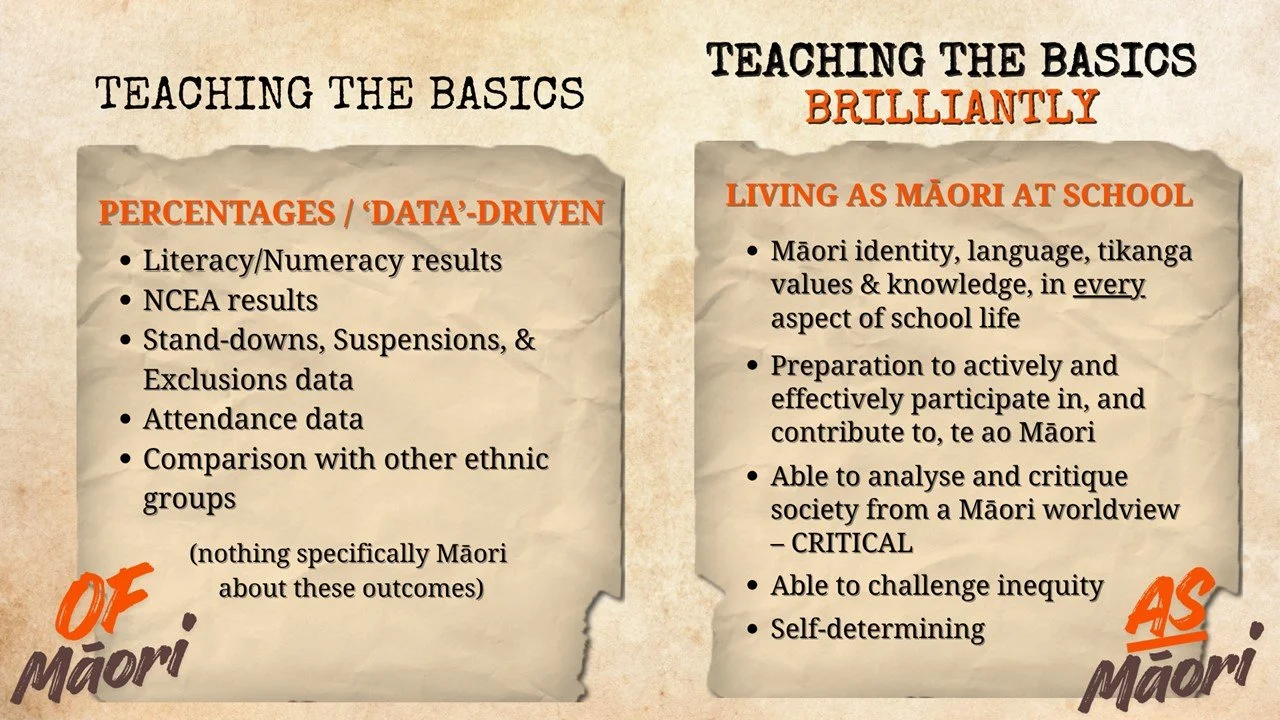

Teaching the Basics, Brilliantly

Fast forward to my first principal’s job in 1994, five years after the major 1989 reform of Tomorrow’s Schools, which introduced a system of neoliberal, self-managing schools, shifting administrative and financial power to local boards of trustees.

Yes, we became managers, accountants, data-driven, competitive, and business-focused, but those who now write the reviews and reports on its failure weren’t teaching 100% Māori and Pasifika kids in Otara! The autonomy of Tomorrow’s Schools gave the community of my school, for the first time, the power to shape learning that suited their children, that rejected the racist approaches they had been subjected to as learners themselves.

Over the next 20 years we did just that—to use your slogan, Erica, teaching the basics brilliantly—the basics of being Māori, or Samoan, Tongan, or Cook Islands Māori, the basics of identity, the basics of developing the critical consciousness to reclaim rights, to stand up for injustice, to speak out—the basics of whānau and community—to develop what we called “Warrior-Scholars.” We used every tool Tomorrow’s Schools put at our disposal to—basically, and brilliantly—eradicate white spaces: the Parents’ Advocacy Council, the process to change the school's status and class structure three times, the contestable funding, and the voice and power of a community. We deliberately broke many rules along the way, never losing sight of our end goal—to be different on purpose because our Māori and Pasifika kids had the absolute right to an education that put their needs, and their right to learn as who they were, first.

We built a whole new school, deliberately planned to replicate the open-plan ‘modern learning environment’ of the original buildings, built in 1980, because they were perfect for the learning we developed, centred on whānau, and as close to home as we could get it.

Stack that intention up against the current landscape that is hell-bent on removing Māori voice, Māori choice, Māori language, Māori environments from our education system—and rebuilding those walls.

Let’s be honest — this has nothing to do with raising standards. It’s about clawing back control of the narrative and the system to appeal to the elite. Back in 2013, I wrote:

To “name the white spaces” in our schools we have to talk about white privilege and white supremacy without taking these terms personally. We have to ask the hard questions about the purpose of schools, whose knowledge counts, who decides on the norms we expect our youth to strive to achieve, who decides on literacy and numeracy as the holy grail and almost sole indicator of achievement and success? (Milne 2013).

Those questions haven’t changed!

E is for [White] Elephant

On my Pātaua phonics chart, E was for Elephant, so let’s talk about the very white elephant in Erica’s toolbox, that is literacy and numeracy—structured or not—and the manufactured crisis that she would have us believe she just discovered all by herself.

As we have seen all week, with the completely rewritten, without consultation, curriculum released, Erica’s solutions are more antelopes, llamas! The mandatory one hour (“on average”) of literacy and numeracy a day, is framed as getting tough on ‘failing schools,’ with the instruction that “Teachers will deliberately and purposefully dedicate time to teaching these core skills.” What do they think teachers were already doing?

Let’s be clear, this is not ‘redesigning’ at all. It is yet another example of a system doing exactly what it has always been designed to do, to create, and even worse, tolerate, a social hierarchy, inequality, and inequity not far removed at all from our earlier policies of integration and assimilation that aimed to make us all the same i.e., all White.

Erase, Rename, Repeat

Once again – been there, done that! This is not a new fight, just a government using schools as a weapon in the process of colonisation and assimilation—it’s just one long loop—erase—rename—repeat!

If all we needed was a relentless focus on literacy and numeracy, why didn’t it work when John Key’s fifth National Government implemented National Standards between 2010 and 2017?

Professor Georgina Tuari Stewart calls the current reintroduction of testing, using euphemisms like ‘checkpoints’, ‘phonics checks’ and ‘progression monitoring’ as “the return of National Standards by stealth” and labels the tests “useless and clearly harmful to children.

We know very well just which children were harmed by the National Standards testing regime—not your mokopuna, Erica!

Brilliantly White and Race-Blind

Why won’t your “teaching the basics brilliantly” work any better, Erica? Because it is teaching the basics brilliantly, white, and race blind.

Anti-racism research calls out race-neutral policies, which are endemic in the coalition government’s decisions, as failing to reverse the gaps and barriers that exist because of structural racism and as a threat to racial equity for indigenous and minoritised groups. The research finds that only race-conscious policies—policies that may disproportionately help indigenous and minoritised communities can dismantle those structural barriers. (Jayakumar & Kendi, 2023; Maye, 2022). We know we won’t see any of those anywhere in the coalition government’s education policy.

This deliberate elimination of so-called ‘race-based’ policies by the coalition government to attract and placate their right-wing voter base simply says we couldn’t care less about addressing racism and inequity. In fact, we’ll not only happily encourage it, but we’ll hide behind seemingly benevolent but still racist statements about the common good and working for all ‘New Zealanders’.

What Literacy DOES Work?

On the 19th of November last year, my oldest great-granddaughter, Atareta, stepped up to the microphone in front of Parliament Buildings alongside the amazing Hana Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke. At 14 years old and to an audience of over 80,000 flag-waving protesters, this is what Atareta said:

As rangatahi Māori. We’re watching… and learning.

We’re watching Hana-Rawhiti and learning that as the youngest person in parliament in the world - you can make people take notice.

We’re watching older people in parliament who don’t listen and don’t change their minds - and we’re learning that there has to be a better way.

We’re watching other young people who have helped organise this hikoi - and we’re learning that we don’t have to wait until we’re older to find our voice and have something to say.

Think of Atareta’s words, not only as a challenge to members of parliament, but to us in our schools and classrooms.

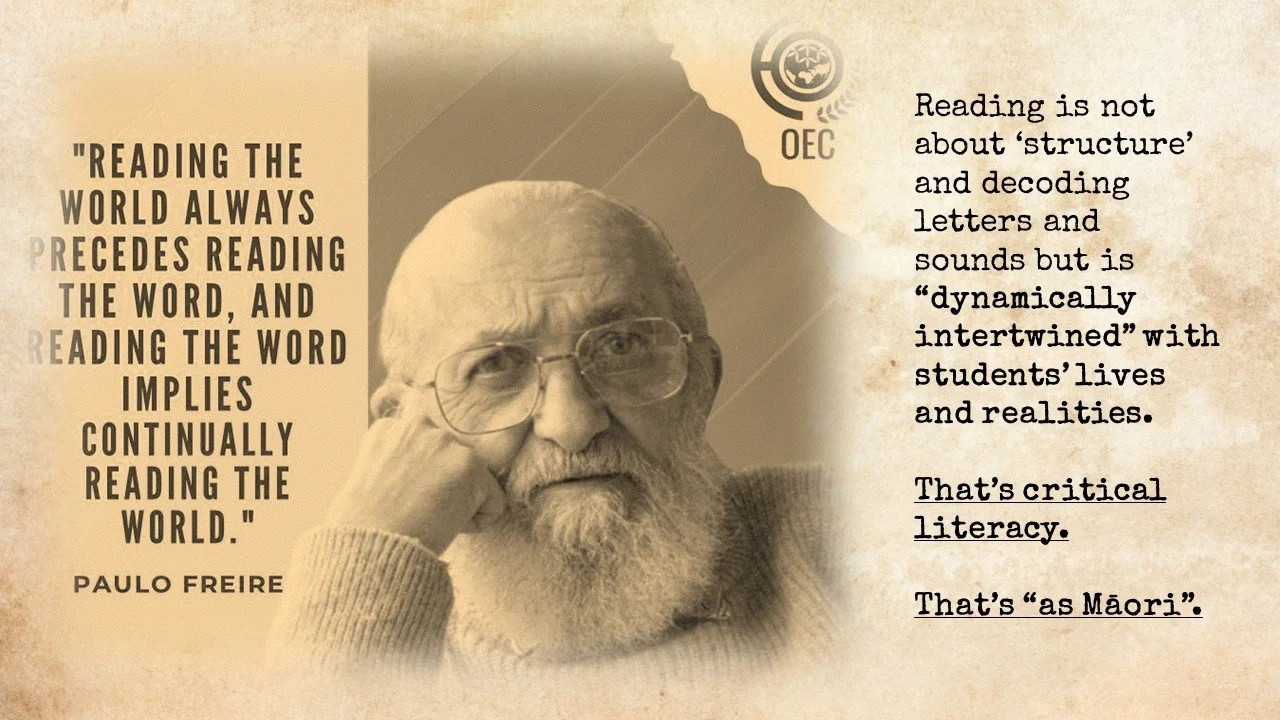

Our rangatahi, on the hikoi, in their classes, and in their homes, listened to powerful speakers—tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti alike—and then learned about writing submissions against the Treaty Principles Bill, learning skills of argument, persuasion, points of view, research, critical analysis, and increasing their vocabulary—in te reo Māori and English. They learned what Paulo Freire called “reading the world,” that is, understanding the political context of your world before you can effectively “read the word.” That means, Erica, that reading is not about ‘structure’ and decoding letters and sounds but is “dynamically intertwined” with students’ lives and realities.

That’s critical literacy. That’s “as Māori”.

But instead of understanding that, Erica, what did you do? You clearly demonstrated again how little you know about education when you said children should be in school and not participating in the hikoi. You showed us that again with your recent PR exercise about the unverified “success” (after 8 months) of your phonics regime. You see, in 63 years in education, I have never met a parent whose primary measure of success for their children was decoding words out of context—until you.

Learning from our Past Mistakes

So, in my long trip down memory lane, what can we learn from the lessons and mistakes of the past?

You would hope we would learn not to repeat them, but clearly, this is not the case. Unfortunately, there is one crucial mistake that we, as a profession of educators, keep repeating. I wrote this in a previous blog post, and unfortunately, I see no reason to change it!

What frustrates me the most is our silence. Thank goodness for this Collective and the writing and analysis of AEC members. Kudos too to the minority of principals who will choose to take a stand and either refuse to implement policy that will damage children, or who will at least adapt their implementation to suit their communities and whānau. How are we supporting them?

Those principals and groups who stood up against the National Standards testing debacle were targeted by a vindictive Minister of Education at great personal and professional cost (Milne-Ihimaera, 2018). They will tell you they would do it all again, but probably not as publicly!

Neutrality is a Position

Neutrality is a position. Silence is not neutrality, it’s collusion! It’s the choice we make to roll over and play dead and just allow racist changes to happen unchallenged. The unfortunate truth is that when successive governments introduce change without any credible evidential base, when individual politicians and advisers misuse power and demand we ‘jump’ to suit their flawed policy promises, the majority of us simply ask ‘how high?’ We might complain to each other, but inevitably we start implementing the change, aligning ourselves with the minority of educators who think they might work, when history and experience tell us they will not. As a profession, we seem unable to unite, so divided we fall. We tolerate, then perpetuate, the harm this direction will do to mokopuna Māori and we accept they will be collateral damage. Obviously, only some of our mokopuna matter and, until that changes, we’ll just continue to be complicit in the damage.

The greatest mistake we can collectively make is believing the new reforms are an attempt to 'fix' a failing system. They are an attempt to reassert control and normalise assimilation by erasing the hard-won gains in Tiriti-led and Māori-centred education. And we have been here before multiple times!

There are some heartening examples lately that show collective strength and of course, many teachers, in this room and all over the country, are putting in a huge amount of work.

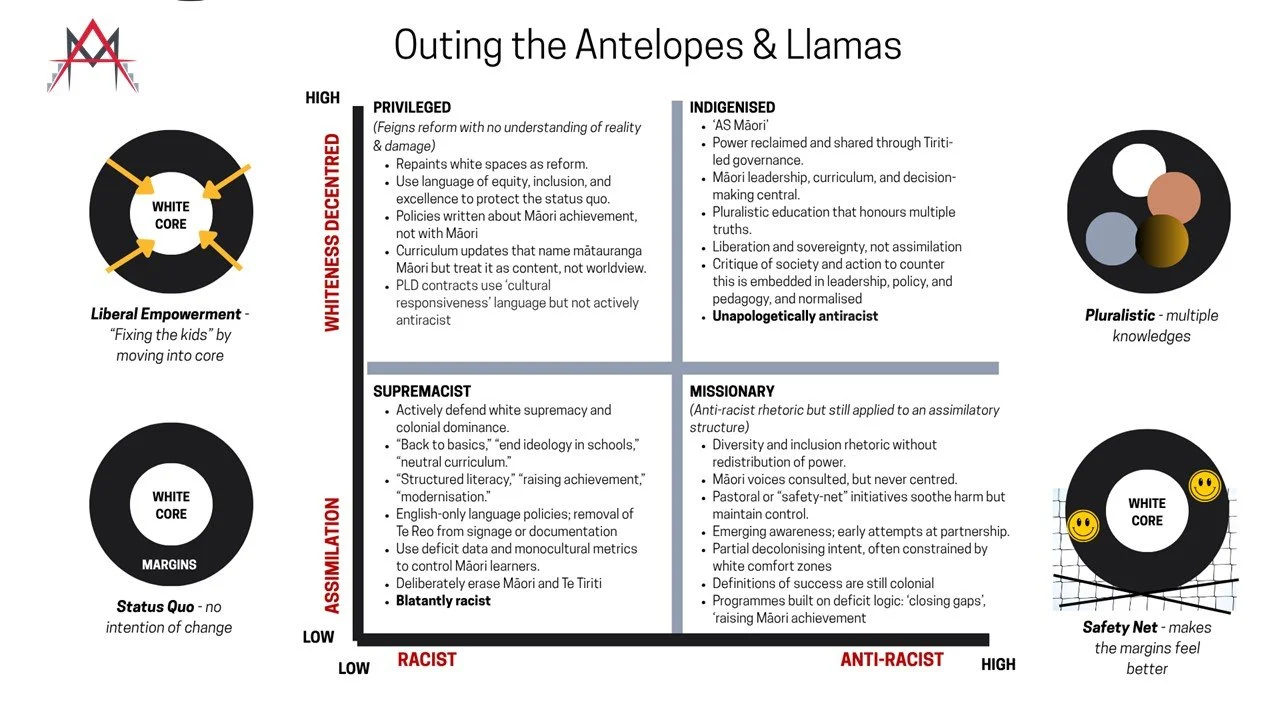

But, the honest truth is—it’s not enough! I know, in this audience, I’m preaching to the converted, but I want to leave you with an image that I encourage you to use as a mirror, to reflect on your thinking and your practice back in your schools and organisations, and to check if any antelopes and llamas are still lurking there.

Around the edge of this slide are the Social Transformation diagrams from ‘An Educator’s Guide to Changing the World’ (Curry-Stevens) that I have used many times. These four diagrams are aligned with the quadrant in the centre—a conceptual framework for determining our position on axes from Assimilation to Whiteness-Decentred, and Racist to Antiracist.

Starting at the bottom – the low/low quadrant, we have the status quo, definitely the norm, where the white core is the central place of power, occupied in our case, by Pākehā, and outside that core are all those we minoritise. It’s a blatantly racist model with no intention of changing – in fact, currently doubling down on our racism and supremacy. Most of the current changes to our education system are firmly located in this box.

Antelopes and llamas thrive and multiply in this space—and our mokopuna deserve better!

Moving up to the top-left, we have the Liberal Empowerment model. This is a privileged position where we pay lip service to reform that sounds as if it might decentre whiteness, but it never relinquishes control.

Often, here we have no clue about the realities of the children in the margins, or the damage we inflict on them, as Hana told us so eloquently yesterday.

Here, we talk about culturally responsive pedagogy rather than critical, culturally sustaining work. We hold equity, not sovereignty, up as the holy grail, and our goal, with a plethora of programmes like PB4L, inclusion, growth mindset, grit, and yes—structured literacy & maths, knowledge-rich approaches—that are ALL about ‘fixing the kids, ignoring the fact that we damaged them in the first place!

The Liberal Empowerment model is about improving the education of Māori and the other groups we relegate to the sidelines —by helping them move into the core, if they learn our rules. It’s about teaching them to play OUR game, not about changing the game altogether.

In this space, we expect all of our mokopuna to be antelopes and llamas!

At the bottom right, we have the missionary or saviour position that, unfortunately, many of us get to, then stop! We are high on anti-racist rhetoric and intent, but low on actually decentering whiteness. And that’s my challenge to us! How far are you REALLY prepared to go?

The antelopes and llamas lie in wait in this space.

They hide in our definitions of success and achievement, even more entrenched in our curriculum now than they were before. They sneak out in our assessment practice, and although we often have the best of intentions, we retreat back to our comfort zone, which is still our largely assimilationist model.

We mean well, the children in our margins might feel a little better, but we haven’t shifted that white target much at all.

The fact remains that nationally close to 90% of Māori children are exposed to the damage that is caused INSIDE that white core space, which, it is glaringly obvious, fails to meet their education needs, and pretends not to understand how hegemony works to perpetuate the dominance of the core until eventually we think it is “normal” and we no longer question it.

Any inclusion of Māori learners into our white space cannot be anything other than assimilation, so if that is still our goal, why don’t we just say so?

Solórzano and Yosso assert that, according to cultural deficit storytelling (which is what we are being fed under the guise of “knowledge-rich” reform), “a successful student of color is an assimilated student of color.”

If We Genuinely Want to Make a Difference

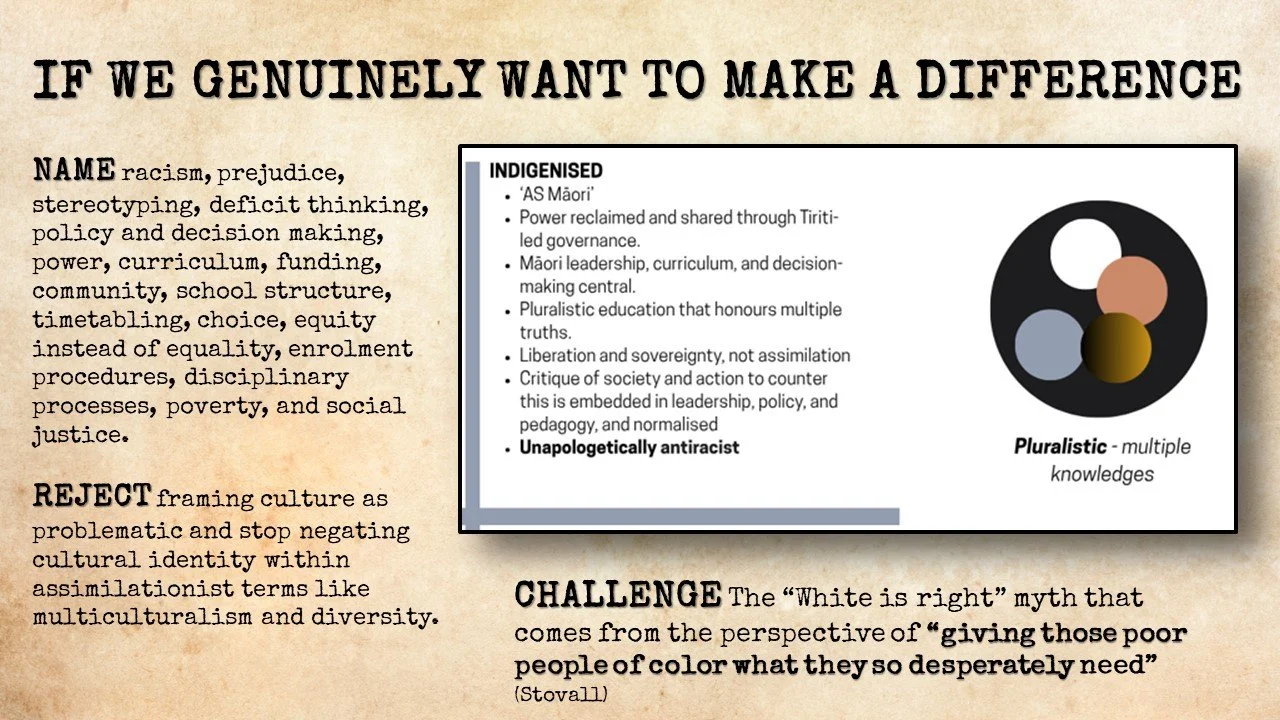

If we genuinely want to make a difference, to reach the top right, pluralistic, quadrant – we have to be committed to moving from a deeply dehumanising, racist, education system to a pro-actively anti-racist, Tiriti-led system taking intentional action to counter racism, hegemony, privilege, and all the other barriers Māori learners encounter as they try to navigate our education system at every level.

We have to name racism, prejudice, stereotyping, deficit thinking, policy and decision making, power, curriculum, funding, community, school structure, timetabling, choice, equity instead of equality, enrolment procedures, disciplinary processes, poverty, and social justice.

We have to reject framing culture as problematic and stop negating cultural identity within assimilationist terms like multiculturalism and diversity.

We have to challenge Eurocentric solutions that perpetuate the myth that “white is right,” and come from the perspective Stovall (2006) calls, “giving those poor people of color what they so desperately need.” (Milne, 2013)

Those of us who are not Māori have to do this work ourselves. It is not the job of Māori to undo colonisation or help us fix our racism or our privilege. Undoing colonisation is the job of the coloniser – that’s US.

On the other hand, re-indigenising the curriculum is not the job of white educators. Re-indigenising is the right of Māori to determine what matters for their children’s education, to decide which cultural knowledge, language, and values need to be prioritised in schools, and it is our role to get out of the way of that.

Where All our Mokopuna Matter

In the top-right social transformation diagram, we intentionally break the stranglehold of that white core—to shift from practices that are still colonial and racist to practices that genuinely recognise all knowledge as valid and equal, and power is genuinely negotiated, navigated, and shared. Māori must be able to determine the shape and growth of this transformation for our Māori learners.

The top-right box is the counter to scripted curriculum purchased from overseas, to programmes that preach as the United States did—No Child Left Behind (that Native Hawaiian teachers aptly renamed No Child Left Brown). In the top-right box, we have finally dealt to the antelopes and llamas, who now have a place no more important than any other knowledge, where A could be for antelope and/OR ārero, where ALL our mokopuna matter.

When I think back to that one classroom in Pātaua and the children I grew up with, I realise this fight isn't just about our mokopuna today. It's about honouring the generations that we have intentionally sacrificed to the antelopes and llamas in the past.

In my whānau, as in countless others, it has taken three generations to reclaim the language and the knowledge that was deliberately stolen. We are not going to let that go! You know, the thing about old age is it makes you grumpy! I don’t agree that this is a slow game, or a marathon – it’s beyond urgent and I am not prepared to let one more mokopuna wait one more generation while we get our act together.

If all it takes is a Book, Erica

If all it takes to mandate massive change in our education system, Erica, is for you to read a book, I have another one for you to read on your next beach holiday.

In How to be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi argues that without the capacity for honest self-reflection and critical thinking, we'll continue to swear we "don't have a racist bone" in our body “all while racism and white supremacy persist unchecked, destroying communities and lives”.

It is no longer acceptable or enough to ‘not be racist’. We must be actively anti-racist, build anti-racist structures and institutions, and be actively engaged in learning how to do that.

If your obsession with improving PISA, PIRLS, and TIMSS outcomes is the answer, Erica, what is the question?

Kendi has those:

What if, all along, our well-meaning efforts at closing the achievement gap has been opening the door to racist ideas?

What if different environments actually cause different kinds of achievement rather than different levels of achievement?

What if our educational system focused on opening minds instead of filling minds and testing how full they are?

What if the way we measure intelligence shows not only our racism but our elitism?

What if? Indeed! The bottom line is, we are measuring the wrong stuff!!

The job of those of us who benefit from the 'whitestream' is to ensure that for the first time in our history, the education system, from policy to classroom, reflects the courage of our mokopuna, like Atareta—the courage to read the world and take action to change it.

But will we? Really? We have been here too often before; this has to be the very last time.